Content outline provided by Dr. Maroma Potenciana

Anatomy and Physiology of the GIT

Functions of the GIT

- Ingestion: taking in food.

- Secretion: hydrochloric acid, bile, enzymes (catalysts)

- Digestion: breaking food down into nutrient molecules.

- Mechanical food breakdown through mastication, churning of the stomach, and segmentation in the small intestine. This prepares food for further degradation by enzymes.

- Chemical breakdown of food by enzymes. Carbohydrates are broken down into monosaccharides, proteins are broken down into amino acids, and lipids are broken down into fatty acids and glycerol.

- Motion: motility, propulsion; movement of food products along the alimentary canal

- Peristalsis: wave-like contractions of the GIT to move food.

- Segmentation: movement of food back and forth to foster mixing in the small intestine.

- Absorption: the movement of nutrients from the food into the bloodstream

- Defecation: the excretion of indigestible wastes from ingested food

The Alimentary Canal

The alimentary canal and organs are a part of the gastrointestinal system, which consists of all body parts which make up the hollow tube that starts from the mouth to the anus, which spans ~9 meters in length.

- Mouth: ingestion and digestion begins with the mouth, where mastication (chewing) of food starts, which converts food into bolus by mixing chewed food with saliva. The tongue allows for swallowing, and is covered by taste buds, which allow for taste.

- Buccal Mucosa: the mucous membrane lining the inside of the mouth.

- Lips: pink-rid, external surface of the mouth.

- Cheeks

- Hard & Soft Palate: forms the roof of the mouth.

- Uvula

- Vestibule

- Oral Cavity Proper

- Tongue: a muscle involved in speech, taste, and mastication.

- Tonsils: divided into the palatine and lingual tonsils

- Pharynx: a passageway for food, fluid, and air into the esophagus or to the trachea. For food transportation, it moves from the mouth posteriorly into the oropharynx, then inferiorly into the laryngopharynx, which then continues into the esophagus. Superior to the oropharynx is the nasopharynx, which is connected to the nasal cavity. “Swallowing” occurs in the pharynx.

- Food is propelled into the esophagus from the pharynx by two muscles moving in a peristaltic manner: the longitudinal outer layer and the circular inner layer

- Esophagus: a ~10 inch long pipe-like structure that transports food from the pharynx to the stomach, passing through an opening, the diaphragmatic hiatus. It utilizes slow, rhythmic movements of the esophageal muscles in order to move food into the stomach. This is known as peristalsis. The trachea contains sphincters at both ends to inhibit reflux:

- Upper esophageal sphincter (UES): closed at rest to prevent movement of air in the esophagus.

- Lower esophageal sphincter (LES): closed at rest to prevent reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus.

- Stomach: the stomach is a C-shaped organ on the midline and left side of the abdominal cavity. It serves as a temporary storage tank for food being able to contain ~1.5L, and where carbohydrate digestion continues. Protein digestion also begins. The stomach converts bolus into chyme, taking in food from the cardioesophageal sphincter (gastroesophageal junction) and releasing it into the small intestines through the pyloric sphincter.

- Cardial (cardia): the inlet, named because of its proximity to the heart.

- Fundus: the expanded portion lateral to the cardiac region.

- Body (corpus): the middle portion.

- Greater Curvature: the convex lateral surface of the stomach.

- Lesser Curvature: the concave medial surface of the stomach.

- Pylorus (antrum): the funnel-shaped terminal end of the stomach also having a pyloric sphincter that controls the movement of chyme into the small intestines.

- Rugae: folds of the stomach, which allow for expansion of the stomach. The stomach can expand to hold around a gallon (4L) of food when full.

- Omenta: fused peritoneal folds that connect the stomach and duodenum with other abdominal organs. There are two omentum that attach to the stomach:

- Lesser Omentum: the double-layer of the peritoneum, which extends from the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach.

- Greater Omentum: another extension of the peritoneum; a cover for the abdominal organs, with fat for insulation, cushioning, and protection. Connects the stomach and the transverse colon.

- Stomach Mucosa: the simple columnar epithelium composed almost entirely of mucous cells. The mucous cells produce bicarbonate-rich alkaline mucus.

- Gastric Pits contain gastric glands that secrete gastric juice. This juice includes intrinsic factor (IF) that allows for the absorption of Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin).

- Chief Cells produce protein-digesting enzymes (pepsinogens)

- Parietal Cells produce hydrochloric acid that activates enzymes.

- Mucous Neck Cells produce thin acidic mucus (separate from the mucosal alkaline mucus)

- Enteroendocrine Cells produce local hormones such as gastrin.

- Gastric Secretion: the processes involved in stimulation of the digestive activities of the GIT.

- Cephalic Phase: stimulation of the GIT via sight, smell, taste, or even imagination of food. The vagus and GI nerve plexuses initiates secretory and contractile activities.

- Gastric Phase: stimulation of the GIT via the presence of food in the stomach. Gastric juice (made up of hydrochloric acid, hormones, and enzymes) act on food (bolus) to convert it into chyme.

- Gastrin (G) Cells produce Gastrin, which promotes the secretion of hydrochloric acid and pepsinogen.

- Hydrochloric Acid converts pepsinogen into active pepsin for protein digestion.

- Mucus and Bicarbonate secretions protect the stomach from mechanical and chemical damage.

- Intestinal Phase: once chyme passes into the intestines, the duodenum produces secretin, which inhibits further acid production and decreases gastric motility.

- Small Intestines: the small intestines serve as the major absorptive organ. It is the longest by far, spanning from 4 to 8 meters in length (up to 1.5 times in length after death). It connects the pyloric sphincter and the small ileocecal valve (beginning of the colon; large intestines). It is suspended from the posterior abdominal wall by the mesentery. Enzymes break down chyme into its smallest form, where it can be absorbed into the bloodstream. Enzymes are transported into the small intestines through:

- Hepatopancreatic ampulla is the location where the main pancreatic duct and bile ducts join.

- Pancreatic Ducts: intestinal cells and pancreas enzymes are carried to the duodenum.

- Bile Duct: bile, formed by the liver, into the duodenum. The bile duct’s exit is closed by the sphincter of Oddi. It only opens in response to a meal.

- Subdivisions of the Small Intestines

- Duodenum, the starting C-shaped portion of the small intestines continuous with the pylorus (~30 cm long; 1 feet), which is where enzymes are deposited from the liver and pancreas. Carbohydrates and proteins are mainly absorbed in here and the jejunum. The duodenum also produces enzymes and hormones:

- Secretin, an inhibitor for gastric production and motility. It also stimulates pancreatic juice and bile secretion.

- Pancreozymin, a stimulant for pancreatic juice secretion. Triggered by the presence of hydrochloric acid and peptides.

- Cholecystokinin, a stimulant for secretion of pancreatic enzymes and bile in the gallbladder. Triggered by the presence of amino acids and fatty acids.

- Jejunum, the main site of lipid absorption. It is approximately 8’ in length.

- Ileum, the largest portion of the small intestines ranging from 8’ to 12’, taking up the last ~3/5ths of the small intestines where it ends in the ileocecal canal (ileocecal valve), the beginning of the large intestines. It absorbs Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin), bile salts, and other undigested products. All segments work to absorb water and electrolytes.

- Duodenum, the starting C-shaped portion of the small intestines continuous with the pylorus (~30 cm long; 1 feet), which is where enzymes are deposited from the liver and pancreas. Carbohydrates and proteins are mainly absorbed in here and the jejunum. The duodenum also produces enzymes and hormones:

- Structural Modifications

- The small intestines have an increased surface area for food absorption. This is achieved with the villus, microvillus structures and plicae circulares (circular folds). These are numerous at the start of the small intestines but decrease in number by the end small intestine.

- Villi (finger-like projections) increase the absorptive capabilities (surface area) of the intestines. Microvilli are smaller projections of the plasma membrane on the villi.

- Plicae Circulares (circular folds) are the deep folds of the mucosa and submucosa, also for increasing the surface area of the intestines.

- Peyer’s Patches are lymphatic tissues located in the submucosa that increase in number as you reach the end of the small intestine. These serve as part of the lymphatic system. The increase in number can be attributed to the increased prevalence of bacteria in the residue reaching this part of the small intestine.

- The small intestines have an increased surface area for food absorption. This is achieved with the villus, microvillus structures and plicae circulares (circular folds). These are numerous at the start of the small intestines but decrease in number by the end small intestine.

- Large Intestines: starting from the ileocecal valve (cecum) to the anus, it is shorter than the small intestines at ~1.5m long, but is larger in diameter. The large intestines are also held in place by the mesentery. The large intestines are responsible for fluid and electrolyte absorption, vitamin production and absorption, and excretion. The breakdown of waste products is majorly influenced by the colon’s gut microbes, especially in undigested or unabsorbed proteins and bile salts.

- There are two colonic secretions: an electrolyte (mainly bicarbonate; alkaline) solution to neutralize the waste products and mucus for protection, lubrication, and stool forming.

- The intestinal epithelium is the first line of defense against pathogenic microorganisms, containing innate immune cells (macrophages, dendritic cells, granulocytes, mast cells, and a role in T-cell responses).

- Peyer’s Patches are lymph nodes found in the gut, and have a role in antigen processing and immune defense response.

- Cecum: the sac-like beginning of the large intestine. Hanging inferior to the cecum is the appendix (commonly referred to as a vestigial organ), which is an accumulation of lymphoid tissue that sometimes becomes inflamed (appendicitis).

- Colon: the main body of the large intestines; subdivided into three (main) parts, which ends in the sigmoid colon, rectum, anal canal, and anus:

- Ascending Colon: travels up the right side of the abdomen and makes a turn at the right colic (hepatic) flexure.

- Transverse Colon: travels horizontally across the abdominal cavity and turns at the left colic (splenic) flexure.

- Descending Colon: travels down the left side of the abdomen.

- Sigmoid Colon: named because of its shape, it is an S-shaped region of the large intestines that enters the pelvis, connecting to the rectum.

- Diverticulum: small outpouching segments of the GI tract, commonly in the colon. These may become infected with feces and bacteria, resulting in diverticulitis.

- Rectum, Anal Canal: located in the pelvis, where feces are stored for excretion.

- Anus: the colon’s stoma, where feces passes through for excretion. It is normally closed with various muscles and sphincters

- External Anal Sphincter: formed by skeletal muscle and can be controlled voluntarily.

- Internal Anal Sphincter: formed by smooth muscle and moves involuntarily.

- Goblet Cells are found along the entirety of the small and large intestines, which produce alkaline mucus to serve as lubrication for passing substances.

- Teniae Coli: the muscularis externa layer of the colon (made of three bands of muscle). These are what give the colon its sac-like appearance, the haustra.

- Anus: the colon’s stoma, where feces passes through for excretion. It is normally closed with various muscles and sphincters

Layers of Tissue in the Alimentary Canal Organs

- Mucosa: the innermost layer, moist membrane made up of:

- Surface epithelium, mostly made of simple columnar epithelium (except for the esophagus, which is made of stratified squamous epithelium) (Also read: Body Tissues)

- Small amounts of connective tissue (lamina propria) and a scanty smooth muscle layer. This lines the cavity (hollow part) of the alimentary canal, known as the lumen.

- Submucosa: just under the mucosa, it is made up of soft connective tissue that contains the blood vessels, nerve endings, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), and lymphatic vessels.

- Muscularis Externa: made up of smooth muscle with an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer, which work together for peristalsis.

- Serosa: the outermost layer of the wall; this contains a layer of flat serous fluid-producing cells. Divided into the visceral and parietal peritoneum.

Innervation of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems influence the GIT.

- In general, the sympathetic nerves exert an inhibitory effect (decreasing gastric secretions, motility, and constriction of the sphincters and blood vessels) on the GIT

- The parasympathetic nerves increase peristalsis and secretory activities. All sphincters relax under the influence of the parasympathetic nerves except for the UES and External Anal Sphincter (they are under voluntary control)

Alimentary Canal Nerve Plexuses

There are two intrinsic nerve plexuses that serve as a part of the autonomic nervous system. They act to regulate the mobility and secretory activity of the GIT organs:

- Submucosal Nerve Plexus

- Myenteric Nerve Plexus

Accessory Digestive Organs

- Teeth: these are used for mastication (and speech) of food into smaller fragments, beginning its conversion into bolus.

- Deciduous Teeth: also known as “baby” or “milk” teeth, these are the first set of teeth that grow in children. By age 2, a child will have 20 teeth, starting from the lower central incisors that grow by 6 months of age. These will start to shed by 6 years to 12 years of age.

- Permanent Teeth: replacing the deciduous teeth from 6 to 12 years of age, with 32 total teeth if all wisdom teeth are present.

- Classification:

- Incisor Teeth: are chisel-like, and are used for cutting.

- Canines (eyeteeth): are pointed; they are used for tearing and piercing.

- Premolars (bicuspids) and Molars: have flat surfaces, and are used for grinding.

- Regions of Teeth

- Crown: the exposed part of the tooth appearing out from the gingiva (gums).

- Enamel: the material covering the crown; superficial layer of the crown.

- Dentin: deep material of the tooth, forming bulk of the tooth. It covers the pulp cavity of the tooth.

- Pulp Cavity: the part of the tooth containing nerve endings, blood vessels, and nerve fibers, called the pulp.

- Neck: a transitional region between the crown and the root.

- Root Canal: the connecting part from the pulp cavity to the root of the tooth.

- Root: the part of the teeth that extends into the gingiva (gums).

- Cement: the superficial layer of the root. It is a ligament that attaches the root to the periodontal membrane.

- Salivary Glands: saliva is a mixture of mucus (mucin) and serous fluids. These moisten and bind food together into bolus. It contains salivary amylase (ptyalin) which begins starch digestion, and lysozymes and antibodies that protect against bacteria. Approximately 1 to 1.5 liters of saliva is produced in a day.

- Parotid Glands: anterior to the ears. These are affected by mumps.

- Submandibular Glands: posterior and inferior to the sublingual glands.

- Sublingual Glands: situated just under the tongue. Both these and the submandibular glands empty saliva onto the floor of the mouth through small ducts.

- Pancreas: a soft, pink, and triangular (fish-shaped) gland found posterior to the parietal peritoneum (mostly retroperitoneal), behind the stomach. It extends from the spleen to the duodenum. It is segmented into the head, body, and tail of the pancreas. This produces a wide spectrum of digestive enzymes that break down all categories of food. These enzymes are sent into the duodenum. Alkaline fluids introduced with enzymes neutralizes the acidic chyme from the stomach. The pancreas have areas known as islets of langerhans which have cells (alpha, beta, delta, C) that also produce hormones.

- Insulin: used for moving glucose into cells (transcellular glucose transportation) and inhibits digestion of fats and proteins, consequently reducing blood glucose levels; produced by beta cells.

- Glucagon: counteracts the action of insulin by increasing hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis); produced by alpha cells.

- Functions of the Pancreas

- Exocrine: 80% of the organ is composed of acinar cells that secretes enzymes.

- Endocrine: 20% of the organ is composed of islets of langerhans that secrete hormones (insulin, glucagon).

- Liver: the largest gland (internal organ) in the body, located on the right side of the body under the diaphragm. It consists of four lobes (divided into right and left lobes by the falciform ligament) suspended from the diaphragm and abdominal wall by the falciform ligament.

- Storage: of copper, iron, magnesium, Vitamins B2, B6, B9, B12, and fat-soluble vitamins (ADEK).

- Protection: phagocytic and pinocytic Kupffer cells detoxify xenobiotics and foreign bodies, also aiding in the breakdown of erythrocytes.

- Metabolism: aids in breaking down amino acids forming urea, synthesis of plasma proteins, and the metabolism of carbohydrates and fats.

- In the digestive context, its function is to produce bile. Bile leaves the liver through the hepatic duct and enters the duodenum through the bile duct. Bile is a yellow-green, watery solution containing bile salts, pigments (mostly bilirubin), cholesterol, phospholipids, and electrolytes. Bile is used to emulsify fats.

- Gallbladder: the gallbladder is a green sac found in a shallow fossa in the inferior surface of the liver. It serves as storage for bile if no digestion is occurring, with bile backing up the cystic duct. When in the gallbladder, bile loses its water content, and becomes more concentrated. Once fats enter the duodenum again, it is released for digestion. It is divided into the neck, body, and fundus.

Digestion Processes

- Carbohydrates: carbohydrates that come in the form of starch, polysaccharides, and disaccharides are broken down into smaller forms (lactose, maltose, sucrose, galactose, glucose, fructose) via the mouth’s salivary amylase, the pancreas’ pancreatic amylase, and various brush border enzymes in the small intestines (Dextrinase, Glucoamylase, Lactase, Maltase, Sucrase).

- Protein: protein is broken down starting from the stomach, where pepsin is produced by chief cells, breaking protein down into large polypeptides. The pancreas further contribute trypsin, chymotrypsin, and carboxypeptidase to break down large poly peptides to smaller polypeptides. These are finally converted into amino acids (and some di/tripeptides) in the small intestine by various enzymes (aminopeptidase, carboxypeptidase, dipeptidase).

- Lipids/Fats: fats are emulsified by the detergent action of bile salts from the liver, which allows them to be acted upon by pancreatic lipase. This converts fats into monoglycerides, glycerol, and fatty acids. Fatty acids and monoglycerides enter the lacteals of the villi and then enter systemic circulation via the lymph in the thoracic duct. Glycerol and short-chain fatty acids are absorbed into the capillary blood in the villi and are transported to the liver via the hepatic portal vein.

Summary of Digestion and Absorption

- Digestion: physical/mechanical (mastication, peristalsis, segmentation) & chemical (enzymes) breakdown of food into smaller substances.

- Initiated in the mouth where food mixes with saliva to form bolus and starch is broken down by salivary amylase (ptyelin).

- Swallowing food then passes it into the esophagus where, it is propelled into the stomach by peristalsis. The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes and constricts to let food into the stomach and prevent reflux.

- Swallowing starts as a voluntary action, but ends as a reflex as the epiglottis covers the trachea to prevent aspiration. This reflex is mediated by the medulla oblongata’s swallowing center.

- In the stomach, food is processed by gastric secretions (hydrochloric acid, pepsinogen/pepsin, other hormones and enzymes, which all may add up to ~2.4L in a day with a pH as low as 1) into a substance called chyme. It also functions to destroy most ingested bacteria.

- Pepsin (protein digestive enzyme) is the end product of Pepsinogen produced by chief cells.

- Intrinsic Factor is also produced, combining with Vitamin B12 so it may be absorbed in the ileum.

- Secretions are controlled via regulatory substances such as hormones (gastrin, cholecystokinin, secretin), neuroregulators (acetylcholine, norepinephrine), and local regulators (histamine).

- In the small intestine, carbohydrates are hydrolyzed to monosaccharides, fats to 2-glycerol and fatty acids; and proteins to amino acids to complete the digestive process.

- Duodenal secretions come from the pancreas, liver, gallbladder, and the intestinal mucosa.

- Pancreas secrete trypsin for protein, amylase for starch, and lipase for fats.

- The liver produce bile that is stored in the gallbladder and secreted through the duct of Vater, controlled by the sphincter of Oddi, and regulated by hormones, neuroregulators, and local regulators. Bile emulsifies fats for easier absorption.

- In total, intestinal secretions add up to 4.5L/day, 3 liters from intestinal mucosa, 1 liter from the pancreas, and 0.5 liters from bile.

- When chyme enters the duodenum, alkaline mucus is secreted to neutralize hydrochloric acid; in response to release of secretin, pancreas releases bicarbonate to neutralize acidic chyme.

- Cholecystokinin and pancreozymin (CCK-PZ) are also produced by the duodenal mucosa; stimulate contraction of the gallbladder along with relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi (to allow bile to flow from the common bile duct into the duodenum), and stimulate release of pancreatic enzymes.

- Absorption: intestinal cells to absorb nutrient molecules (monosaccharides, amino acids and fatty acids, while villi increase the surface area for absorption, most especially in the small intestine.

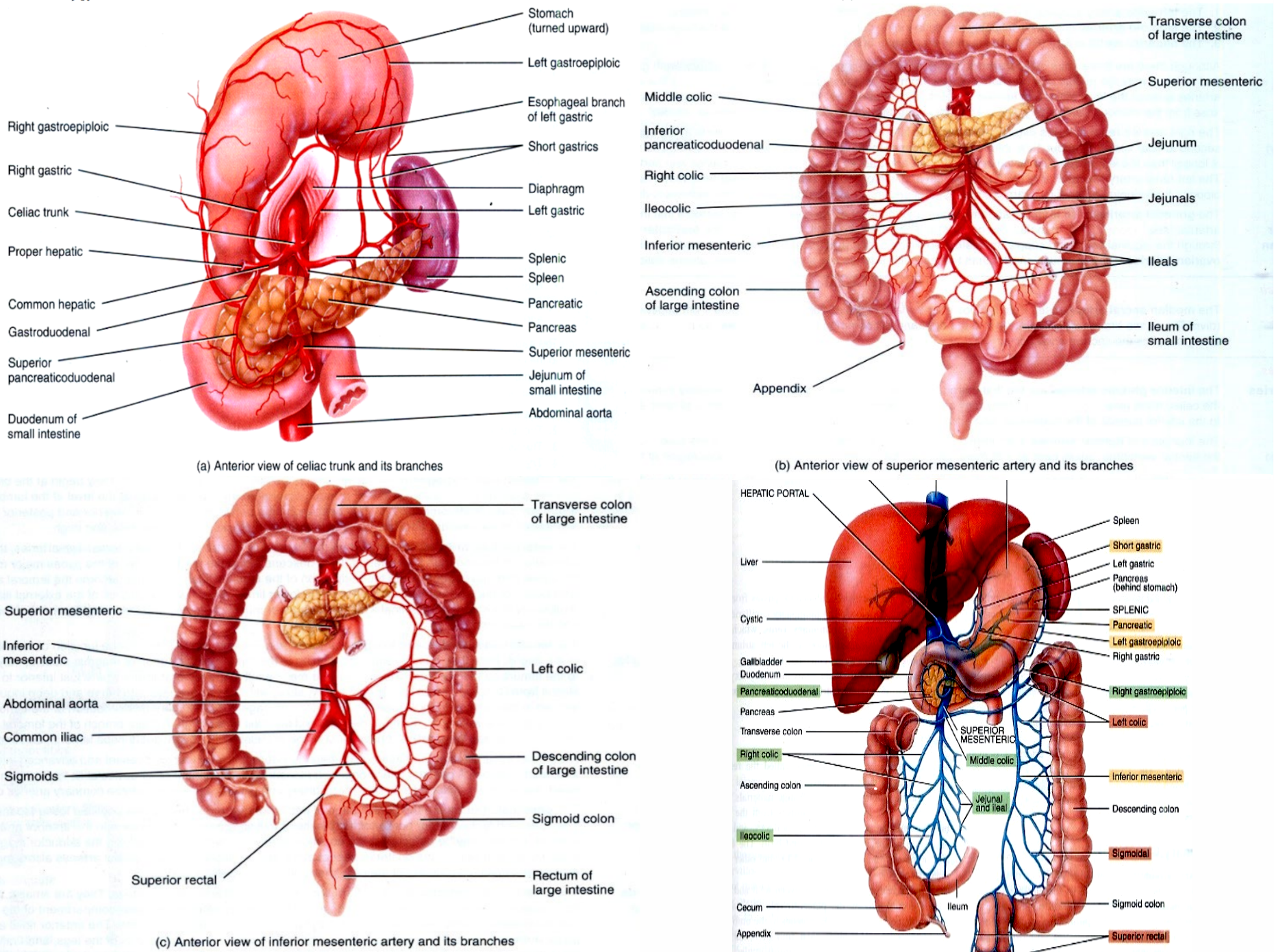

Blood Supply of the Gastrointestinal Tract

The GIT receives blood from arteries along the length of the thoracic and abdominal aorta. For drainage, the portal venous system utilizes five large veins: superior and inferior mesenteric, gastric, splenic, and cystic veins. These all form into the vena portae that enter the liver which then distribute it to the various hepatic veins that terminate in the inferior vena cava.

- Aorta

- Celiac Artery/Trunk

- Right Gastric Artery

- Common Hepatic Artery

- Proper Hepatic Artery

- Gastroduodenal Artery

- Right gastroepiploic artery

- Superior pancreaticduodenal artery

- Left Gastric Artery

- Esophageal Branch of the Left Gastric Artery

- Splenic Artery

- Left gastroepiploic artery

- Short gastrics

- Pancreatic Artery

- Superior Mesenteric Artery

- Middle Colic Artery

- Inferior Pancreaticduodenal Artery

- Right Colic Artery

- Ileocolic Artery

- Jejunals

- Ileals

- Inferior Mesenteric Artery

- Left Colic Artery

- Superior Rectals

- Sigmoids

- Celiac Artery/Trunk

- Inferior Vena Cava

- Superior Mesenteric Vein

- Pancreaticduodenal Vein

- Right, Middle Colic Veins

- Ileocolic Vein

- Jujenal and Ileal Veins

- Right Gastroepiploic Vein

- Hepatic Portal

- Portal Vein

- Splenic Vein

- Short Gastrics Vein

- Pancreatic Vein

- Left Gastroepiploic Vein

- Inferior Mesenteric Vein

- Left and Right Gastric Veins

- Splenic Vein

- Portal Vein

- Inferior Mesenteric Vein

- Left Colic Vein

- Sigmoidal Veins

- Superior Rectal Vein

- Superior Mesenteric Vein

Gut Microbiome

The gut microbiota, alongside its contribution in breaking down waste products, also has a role in vitamin synthesis and immune function. It starts to develop shortly after birth, with a normal gut microbiome established by two years of age. It may be affected by diet, chronic disease, genetics, personal hygiene, infection, vaccinations, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Disruption of normal gut microbiota may result in the overgrowth of potentially pathogenic species.

- Protection of the host against invasion of pathogenic organisms; prevents colonization of pathogens.

- Produces anti-inflammatory metabolites; provokes immune responses.

- Destroys toxins.

Diagnostic Examination of the GIT

Upper Gastrointestinal Series (Barium Swallow)

Barium Enema

Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT)

Endoscopy

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- Proctosigmoidoscopy

PUD

Liver Cirrhosis

Esophageal Varices

GERD

GASTRITIS

DIVERTICULITIS

Ulcerative Colitis

Regional Enteritis

Appendicitis

Peritonitis

Cholelithiasis/cholecystitis

Intestinal Obstruction

URSODEOXYCHOLIC ACID- dissolves the stone

Pancreatitis

Hormones secreted by PITUITARY GLAND

Hyperpituitarism

Hypopituitarism

DI

Sengstaken Blakemore tube

Transphenoidal Hypophysectomy

Etc.

Good luck everyone